Aleutian Islands Campaign

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

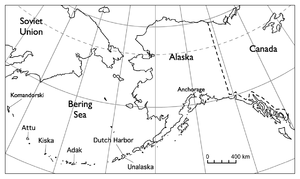

The Aleutian Islands Campaign was a struggle over the Aleutian Islands, part of Alaska, in the Pacific campaign of World War II starting on June 3, 1942. A small Japanese force occupied the islands of Attu and Kiska, but the remoteness of the islands and the difficulties of weather and terrain meant that it took nearly a year for a large U.S. force to eject them. The islands' strategic value was their ability to control Pacific Great Circle routes. This control of the Pacific transportation routes is why General Billy Mitchell stated to Congress in 1935 "I believe that in the future, whoever holds Alaska will hold the world. I think it is the most important strategic place in the world." The Japanese reasoned that control of the Aleutians would prevent a possible U.S. attack across the Northern Pacific. Similarly, the U.S. feared that the islands would be used as bases from which to launch aerial assaults against the West Coast.

The battle is known as the "Forgotten Battle," due to being overshadowed by the simultaneous Guadalcanal Campaign. In the past most western military historians believed it was a diversionary or feint attack during the Battle of Midway meant to draw out the US Pacific Fleet from Pearl Harbor, and was in fact launched simultaneously under the same overall commander, Isoroku Yamamoto. However, historians Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully have made an argument against this interpretation, stating that the Japanese invaded the Aleutians to protect the northern flank of their empire and did not intend it as a diversion.[5]

Contents |

Japanese attack

On June 3, 1942, Japanese bombers attacked Dutch Harbor on Unalaska Island using Kate (Nakajima B5N) bombers from the carriers Junyō and Ryūjō. In bad weather, only half the planes found the target, and little damage was done.[6]

The Japanese invasions of Kiska on June 6, 1942, and Attu on June 7 initially met little resistance from the local Aleuts. Much of the native population of the islands had been forcibly evacuated before the invasion and interned in camps in the Alaska Panhandle.

Allied response

In August 1942, the United States established an air base on Adak Island and began bombing Japanese positions on Kiska.

Battle of the Komandorski Islands

A US Navy cruiser/destroyer force under Rear Admiral Charles "Soc" McMorris was assigned to interdict the Japanese supply convoys. After the significant naval battle known as the "Battle of the Komandorski Islands," the Japanese abandoned attempts to resupply the Aleutian garrisons using surface vessels. From then on, only submarines were used for Japanese resupply runs.

Attu island

On May 11, 1943, the operation to recapture Attu began. Included with the invasion force was a group of scouts recruited from the Alaska Territory, known as Castner's Cutthroats. A shortage of landing craft, unsuitable beaches, and equipment that failed to operate in the appalling weather made it very difficult to bring any force to bear against the Japanese. Many soldiers suffered from frostbite because essential supplies could not be landed, or having been landed, could not be moved to where they were needed because vehicles would not work on the tundra. The Japanese defenders under Colonel Yasuyo Yamasaki did not contest the landings, but rather dug in on high ground away from the shore. This caused bloody fighting: there were 3,929 U.S. casualties: 580 were killed, 1,148 were injured, 1,200 had severe cold injuries, 614 succumbed to disease, and 318 died of miscellaneous causes, largely Japanese booby traps and friendly fire.

On May 29, the last of the Japanese forces suddenly attacked near Massacre Bay in one of the largest banzai charges of the Pacific campaign. The charge, led by Colonel Yamasaki, penetrated U.S. lines far enough to encounter shocked rear-echelon units of the American force. After furious, brutal, close-quarter, and often hand-to-hand combat, the Japanese force was killed almost to the last man: only 28 prisoners were taken, none of them an officer. U.S. burial teams counted 2,351 Japanese dead, but it was presumed that hundreds more had been buried by bombardments over the course of the battle.

Kiska Island

On August 15, 1943, an invasion force of 34,426 Allied troops landed on Kiska. Castner's Cutthroats were part of the force, but the invasion force was made up of units primarily from the United States 7th Infantry Division. The invasion force also included about 5,300 Canadians. The Canadians primarily came from the 13th Canadian Infantry Brigade of the 6th Canadian Infantry Division. The Canadian forces also included the Canadian component of the First Special Service Force, also known as the "Devil's Brigade".

The invasion force landed only to find the island abandoned. Under the cover of fog, the Japanese, who decided that their position in Kiska was vulnerable after the fall of Attu, had successfully removed their troops on July 28 without the Allies noticing. The Army Air Force had been bombing abandoned positions for almost three weeks. On the day before the withdrawal, vessels of the United States Navy fought the inconclusive and possibly meaningless Battle of the Pips 80 miles to the west.

Even though the Japanese were gone before the invasion of Kiska was launched, Allied casualties during the operation nevertheless numbered 313. All of these casualties were the result of friendly fire, booby traps set out by the Japanese, disease, or frostbite. As was the case with Attu, Kiska offered an extremely hostile environment.

Aftermath

Although plans were drawn up for attacking northern Japan, they were not executed. Over 1,500 sorties were flown against the Kuriles before the end of the war, including the Japanese base of Paramushiro, diverting 500 Japanese planes and 41,000 ground troops.

The battle also marked the first time Canadian conscripts were sent to a combat zone in the Second World War. While the government had pledged not to send draftees overseas, the fact that the Aleutians were North American soil enabled the government to deploy them. There were cases of desertion before the brigade sailed for the Aleutians. In late 1944, the government changed its policy on draftees and sent 16,000 conscripts to Europe to take part in the fighting.[7]

The battle also marked the first combat deployment of the First Special Service Force, though they also did not see any action.

Veterans

The 2006 documentary film Red White Black & Blue features two veterans of the Attu Island campaign, Bill Jones and Andy Petrus. It is directed by Tom Putnam and debuted at the 2006 Locarno International Film Festival in Locarno, Switzerland on August 4, 2006.

- Dashiell Hammett spent most of World War II as an Army sergeant in the Aleutian Islands, where he edited an Army newspaper. He came out of the war suffering from emphysema. As a corporal in 1943, he co-authored The Battle of the Aleutians with Cpl. Robert Colodny under the direction of Infantry Intelligence Officer Major Henry W. Hall.

Killed in action

During the campaign, two cemeteries were established on Attu to bury those killed in action: Little Fall Cemetery, located at the foot of Gilbert Ridge, and Holtz Bay Cemetery, which held the graves of Northern Landing Forces. After the war, the frozen tundra began to take back the cemeteries, so in 1946 all American remains were relocated as directed by the soldier's family or to Fort Richardson near Anchorage, Alaska. On May 30, 1946, a Memorial Day address was given by Captain Adair with a Firing Squad Salute and the playing of Taps. The Decoration of Graves was performed by Chaplains Meaney and Insko.[8]

See also

- Attacks on North America during World War II

- Castner's Cutthroats

- Organization of the Imperial Japanese Navy Alaskan Strike Group

- Report from the Aleutians, a 1943 film about the battle, directed by John Huston

- Battle of the Pips

- Paul Nobuo Tatsuguchi

- Aleut Restitution Act of 1988

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Cloe, Aleutian Warriors, p. 321.

- ↑ Cloe, Aleutian Warriors, p. 321–322.

- ↑ MacGarrigle, George L. Aleutian Islands. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-6. http://www.history.army.mil/brochures/aleut/aleut.htm.

- ↑ Cloe, Aleutian Warriors, p. 322–323.

- ↑ Parshall, Jonathan; Anthony Tully (2005). Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1574889246.

- ↑ Banks, Scott (April/May 2003). "Empire of the Winds" American Heritage. Retrieved 7-29-2010.

- ↑ Stacey, C. P.; Canada. Dept. of National Defence. General Staff. (1948). The Canadian Army, 1939–1945; an official historical summary. Ottawa: E. Cloutier, King's Printer. OCLC 2144853.

- ↑ http://www.hlswilliwaw.com/aleutians/attu/html/attu-kia.htm

Books

- Cloe, John Haile (1990). The Aleutian Warriors: A History of the 11th Air Force and Fleet Air Wing 4. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co. and Anchorage Chapter – Air Force Association. ISBN 0929521358. OCLC 25370916.

- Cohen, Stan (1981). The Forgotten War: A Pictorial History of World War II in Alaska and Northwestern Canada. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., Inc.. ISBN 0-933126-13-1.

- Dickrell, Jeff (2001). Center of the Storm: The Bombing of Dutch Harbor and the Experience of Patrol Wing Four in the Aleutians, Summer 1942. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., Inc.. ISBN 1575100924. OCLC 50242148.

- Feinberg, Leonard (1992). Where the Williwaw Blows: The Aleutian Islands-World War II. Pilgrims' Process. ISBN 097106098-3. OCLC 57146667.

- Garfield, Brian (1995) [1969]. The Thousand-Mile War: World War II in Alaska and the Aleutians. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press. ISBN 0912006838. OCLC 33358488.

- Goldstein, Donald M.; Katherine V. Dillon (1992). The Williwaw War: The Arkansas National Guard in the Aleutians in World War. Fayettville: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1557282420. OCLC 24912734.

- Hays, Otis (2004). Alaska's Hidden Wars: Secret Campaigns on the North Pacific Rim. University of Alaska Press. ISBN 188996364X.

Lorelli, John A. (1984). The Battle of the Komandorski Islands. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0870210939. OCLC 10824413.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (2001) [1951]. Aleutians, Gilberts and Marshalls, June 1942 – April 1944, vol. 7 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0316583057. OCLC 7288530.

- Parshall, Jonathan; Tully, Anthony (2005). Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 1574889230. OCLC 60373935.

- Perras, Galen Roger (2003). Stepping Stones to Nowhere, The Aleutian Islands, Alaska, and American Military Strategy, 1867–1945. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 1591148367. OCLC 53015264.

- Urwin, Gregory J. W. (2000). The Capture of Attu: A World War II Battle as Told by the Men Who Fought There. Bison Books. ISBN 080329557X.

- Wetterhahn, Ralph (2004). The Last Flight of Bomber 31: Harrowing Tales of American and Japanese Pilots Who Fought World War II's Arctic Air Campaign. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0786713607.

- Zaloga, Steven J (2007). Japanese Tanks 1939–45. Osprey; ISBN 978-1-84603-091-8.

- Aleutian Islands. World War II Campaign Brochures. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-6. http://www.history.army.mil/brochures/aleut/aleut.htm.

External links

- Logistics Problems on Attu by Robert E. Burks.

- Aleutian Islands Chronology

- Aleutian Islands War

- Red White Black & Blue – feature documentary about The Battle of Attu in the Aleutians during World War II

- PBS Independent Lens presentation of Red White Black & Blue – The Making Of and other resources

- Soldiers of the 184th Infantry, 7th ID in the Pacific, 1943–1945

- ”Attu: North American Battleground of World War II”, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- "Attu,Aleutian Islands, Alaska WW-II KIA [1]

|

||||||||